PUTIN: What 10 Years of Putin Have Brought

An independent expert report by Vladimir Milov and Boris Nemtsov

Unofficial translation from the Russian by Dave Essel

Contents:

Contents:Introduction

Corruption is Eating Russia Up

The Country is Dying Out

Russia: Raw Materials Appendage

Dead-End in the Caucasus

Oh Dear, The Roads

A country of screaming inequality

Pensions Breakdown

Crooked Billions

— Organising a Winter Olympics in the Subtropics

— Crooked Pipelines

— The APEC-2012 (Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation) Leaders’ Summit in Vladivostok

Medvedev and His Results

Conclusion

Introduction

In February 2008, we published our report “Putin — The Results”. It seemed to us back then that it was about time to review what he had brought about now that his presidential term was coming to an end. We assumed that the policies of his successor would differ in at least some ways from those of the previous incumbent. However, Putin continues to play a key role in Russian politics and the course which he followed for 8 year has barely changed.

A great deal has happened since 2008. Russia has plunged into a deep economic crisis. Instead of growing, the economy is contracting. A budget deficit has replaced a former surplus, millions have lost their jobs. Prices, utilities foremost among these, are rocketing. Meanwhile, the number of billionaires has doubled and social and inter-regional inequalities have worsened.

Official propaganda would have it that everything is still fine, the country has weathered the crisis, has conquered terrorism and is beating corruption, that we are proceeding by leaps and bounds along the road of innovation and modernisation, that we are respected around the world, that we are getting wealthier, that there is less poverty, that men and women are bringing forth children, and that “Russia dying out” was a thing of the wild nineties.

The purpose of this report is to tell the truth about what is happening in Russia, to dispel the myths put about by the powers that be, and to relate real information to our fellow-countrymen who for 10 years have not been getting that from the cheerful and frequently false information disseminated by the government-controlled TV and print media.

This report is divided into nine parts. The most important sections are those devoted to corruption in Russia, population issues, social inequality, the economic situation, and the Caucasus question.

Unlike our previous report, which was published in a small print run of 5000 copies and was distributed in the main via the internet, this report is intended for a mass readership and is being published in 1 million copies. The report will be distributed not only in St. Petersburg and Moscow but all over the country – from Vladivostok to Kaliningrad.

Corruption is Eating Russia Up

One of the direst results of Vladimir Putin’s rule has been that Russia has sunk into a dark pit of corruption. Still worse is the fact that corruption in the higher échelons of power in Russia has to all intents and purposes been legalised. Putin’s friends of old, such no-ones before he came to power as Gennadi Timchenko, Yuri Kovalchuk, the Rotenburg brothers, have all become dollar billionaires. It is hardly surprising that the country is beginning to copy its leaders’ modus vivendi.

Back in 2000, we were 82nd in Transparency International’s global corruption rating. (TI is an NGO that fights corruption and carries out research on corruption levels worldwide). By 2009, Russia was seriously down in the league table – in 146th place. Our neighbours on this level were Cameroon, Ecuador, Kenya, Sierra-Leone, East Timor, and Zimbabwe. Today Georgia – at 61st place – ranks way above us in the rating.

Under Putin, theft by officials has gone from a bad situation to a catastrophic one. Transparency International estimates the monetary value of the “corruption market” in Russia at $300 billion. That is one quarter of the country’s GDP!

Our international corruption ratings are confirmed by Russian government data. According to RosStat, the number of crimes recorded under the category “Corruption” rose by 87% between 2000 and 2009 – from 7000 to 13000. (Source: RosStat: Criminality – Crimes Registered by Category.)

These figures are of course dubious: at end 2009 – again according to RosStat – Russia’s army of officisld numbered 870,000, a twofold increase over 1999, when there were 485,000 civil servants. One cannot possibly believe that only 13,000 of those 870,000 bureaucrats take bribes.

The corrupt are for the most part never punished in Russia. According to Chairman of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation V. Lebedev, in 2008 only 25% of persons accused of bribe-taking received prison terms while 65% were given suspended sentences! (From a speech by Chairman of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation V. Lebedev at a meeting of Russian Federation Court Chairmen on 27 January 2009, reported in Kommersant newspaper article of 28 January 2009 entitled “Majority of Those Convicted of Bribe-Taking are Policemen”.)

This is a clear demonstration of how Russia’s “Basmanny Court” justice system works: officials who take bribes are practically immune from serious punishment.

We also never received replies to these questions, which we asked in our earlier reports “Putin: The Results” and “Putin and Gazprom”:

• How come the following were allowed to pass out of Gazprom’s control – Gazfond (the country’s largest private pension fund), Gazprombank (our second largest bank), Sogaz (a major insurance company), Gazprom-Media (the media holding which includes the NTV, TNT, and other media assets)? Why and how did Rossiya Bank and its main shareholder, Putin friend Yuri Kovalchuk, gain control over these assets? Where did more than 6% of Gazprom’s shares, which were on the company’s books in mid 2003, disappear to?

• Why did Gazprom share hundreds of millions of dollars of its annual profits from gas transit and the re-export of Central Asian gas with EuralTransGas and RosUkrEnergo? Who are the beneficial owners of these intermediary companies?

• Why did the state pay Roman Abramovich $13.7 billion for 75% of the shares of Sibneft, which there was absolutely no need for the government to nationalise? A new question arises out of this: why did Gazprom in 2009 decide to pay a further $4 billion to Italian ENI for another 20% of Sibneft shares when Gazprom already owned three-quarters of the company. Financing this purchase led to increased gas prices for Russian consumers.

• Who is the true owner of Millhouse, the company through which Roman Abramovich operates?

• Why do state-owned oil enterprises export a considerable proportion of their oil through Gunvor, which is owned by Putin friend Gennadi Timchenko? How is it that Gunvor, which back in 2000 was an oil-trading bit-player, has during Putin’s time in power gained control over Russia’s oil exports?

• Who is the real owner of SurgutNefteGaz, Gunvor’s largest oil supplier? As a result of our publication in “Putin: The Results” and “Putin and Gazprom” of certain facts regarding the transfer of assets worth over $60 billion out of Gazprom, Alexei Navalny demanded that the General Prosecutor’s Office investigate the matter. He actually received a reply, too: evading the issue, an assistant to the General Prosecutor wrote: “We can find no grounds for the Prosecutor’s Office to become involved”. (Letter ref 73/1-1222-2008 of 14.10.2008.)

Back when we published “Putin: The Results”, talk of Putin’s mighty personal friends with access to billions – Timchenko, the Kovalchuk brothers, the Rotenberg brothers – circulated only as rumours. Now, however, all these people can be found quite officially in the listings of Russian billionaires. According to Forbes magazine, Gennadi Timchenko is 36th in that list, with a wealth of $1.9 billion. Yuri Kovalchuk comes in at #67 with nearly $1 billion. Brothers Arkadi and Boris Rotenberg occupy slots 99 and 100 with a combined wealth of $1.4 billion. (Source: Forbes’ 2010 rating of Russian 100 richest businessmen.)

Putin has installed at the feeding trough not only his closest friends, but their relatives too. Yuri Kovalchuk’s son Boris was, at the age of 29, placed at the head of the Department of National Projects of the Government of Russia, which he ran from 2006 to 2009. When National Projects was rolled up, Boris Kovalchuk was given the post of Deputy Director of RosAtom and in late 2009 sent to head InterRAO, the state monopoly for electricity import/export. Meanwhile, Yuri Kovalchuk’s brother Mikhail heads the Kurchatov Institute [Russia’s leading research and development institution in the field of nuclear energy — Trans.], which the state has been financing in recent years to the tune of tens of billions of roubles.

Another example of nepotism à la Putin comes from billionaire brothers Arkadi and Boris Rotenberg. In the early 1990s, Arkadi Rotenberg helped V. Putin practise judo as his sparring partner (which is why he is often referred to as “Putin’s judo trainer”). Together with the previously-mentioned Gennadi Timchenko, he set up Petersburg’s YavaraNeva judo club of which Putin is the honorary president.

The Rotenberg brothers built their business on supplying pipes and providing building services to Gazprom. This despite the fact that they neither made nor built anything. Back in 2003-2004, Boris Rotenberg was a junior partner in Gaztaged, a company with a turnover of about $1 billion, through which pipe purchases for Gazprom were routed. He later acquired shares in SEPT (North European Pipe Project), a pipe-trading company with a turnover of around $1.5 billion which is going to supply pipes to the North Stream pipeline project. Arkadi Rotenberg controls StroiGasMontazh, a group which in 2008 bought controlling shares in 5 Gazprom subsidiaries making pipelines for the North Stream, the “Olympic” Dzhubga-Lazarevskoye-Sochi, and other pipeline projects. (Article “Friendly Division of Gazprom Spoils”, Vedomosti, 9 March 2010, “Building Giant Gets Personal Trainer”, Kommersant, 2 September 2008.)

Controlling Gazprom, as we can see, has become a nice little earner for Vladimir Putin and his friends. Sadly, Russian gas consumers have to pay for all this: prices to them have risen from an average of 358 roubles per 1000 cubic metres to over 2500 roubles in 2010.

There is reason to believe that all these Timchenkos, Kovalchuks, and Rotenbergs are no more that the nominal owners of their vast holdings and the real ultimate beneficiary is Putin himself.

In 2008, Timchenko’s partner in oil-trader Gunvor, Torbjörn Törnqvist, admitted in a letter to the editor of British newspaper The Guardian that Gunvor does have a “third beneficiary”. But who that is, no one knows. (“Who is Number Three at Gunvor”, Vedomosti, 25 December 2007; “Who is Gunvor’s Third Shareholder?”, Novaya Gazeta, 12 October 2009.)

Timchenko buys up key oil-and-gas assets in Russia. Gunvor has become co-owner of RosNeftBunker, which is building a oil terminal in the port of Ust-Luga. Gunvor is building another oil terminal in Novorossiisk. Timchenko’s Volga Resources fund controls over 20% of Novatek, Russia’s second largest gas extraction company and also about 80% of StroiTransGaz, one of Gazprom’s largest works subcontractors.

Timchenko companies hold licenses to work the massive Angora-Lensk gas field, shares in the giant Yuzho-Tambeisk gas field on the Yamal peninsula, and 30% of the project to develop the Lagansk field in the Caspian Sea. (“Timchenko Expands His Empire and Starts Drilling”, Vedomosti, 4 March 2010).

It is hardly surprising therefore that experts and followers of politics are competing with each other to guesstimate Putin’s personal worth. Is it $20 billion? $30 billion? More?…

Nepotism as a model is now ubiquitous in Putin’s Russia. There was not much to be heard about corruption surrounding Moscow Mayor Luzhkov back in the 1990s. But in 2000, his wife Yelena Baturina became a dollar billionaire and Russia’s richest woman. We wrote of this in our reports “Luzhkov: The Results and “Luzhkov: The Results II”. (See www.luzhkov-itogi.ru)

Baturina ranks #27 with a worth of $2.9 billion in Forbes’ list of Russian billionaires.

Thirty-four-year-old Dmitri Patrushev, son of the former FSB director and now Secretary of the Security Council of Russia Nikolai Patrushev, is VP of VneshTorgBank. His younger brother Andrei Patrushev is an adviser to the Chairman of the Board of Vice Premier Igor Sechin’s RosNeft. Disgracefully, Andrei Patrushev was in April 2007 by an ukase of President Putin (RF Presidential Ukase #545 of 24 April 2007) awarded the Order of Merit “for years of conscientious work” at a time when he been in RosNeft for less than a year following his graduation for the FSB Higher School.

Twenty-nine-year-old Sergei Ivanov, Vice-Premier Sergei Ivanov’s youngest son, was in February 2010 made deputy chairman of the board of Gazprombank, the country’s second largest bank, where he had been working since 2004. Alexandr, Sergei Ivanov’s eldest, is a director of Vneshekonombank, while is father is a member of the bank’s oversight committee. (“Room for the Kids: Yuri Kovalchuk’s Son May Head up InterRAO. How the Children of the Powerful Find Jobs in Russia”, Russian Forbes, 23 November 2009). Alexander, by the way, is the driver who in May 2005 ran over Muscovite Svetlana Beridze, who died of her injuries at the scene. The court decided to close the case “for lack of cause in the actions of the driver”.

Thirty-seven-year-old Stanislav Chemezov, son of RosTekhnologii Head Sergei Chemezov, one of Putin’s mightiest friends, owns shares in I.A.D. Business Industry (field: dual-purpose IT technologies with projects supported by arms-exporter RosOboronExport), in Russian Industrial Nanotechnologies, as well as in several building companies. He is also on the board of directors of AvtoVAZ Energo. (“RosOboronExport Head Sergei Chemezov Not One to Forget Friends”, Russian Forbes, October 2007; “RosOboronExport Looks to Its Own: Chemezov-Junior Joins the Board of AvtoVAZ Energo”, Vedomosti, 21 August 2007).

Thirty-one-year-old Alexei Bogdanchikov, eldest son of the head of RosNeft, worked in RosNeft from June 2004 before moving to work as business development director of gas extraction company Novatek, the company controlled by Putin friend Gennadi Timchenko.

Sergei, thirty-seven-year-old son of St. Petersburg Governor Valentina Matviyenko, became managing director of VTB-Kapital (now VTB-Development), VneshTorgBank’s real estate development arm.

Petr, the thirty-two-year-old son of Foreign Intelligence Head and former prime-minister Mikhail Fradko, is a member of the board and deputy chairman of Vneshekonombank.

When he was “appointed to the post of president” in 2008, Dmitri Medvedev declared that “war on corruption” was his priority. In the two years since then, Russia has dropped still lower in world corruption ratings, bribery is rampant, and levels of nepotism and favouritism unprecedented since the 1990s are there for all to see in the management of state property and funds. The pretend war against corruption began with a ruling that civil servants would have to publish declarations of their incomes and property. But it’s impossible to believe what the leaders of our country say about themselves.

Putin declared that his income for 2009 amounted to 3.9 million roubles (~$125,000). On this income, our prime-minister was able to give a boy shepherd in the Tula region a wristwatch worth $10,500 only magically to be seen wearing a new model of the same a few days later. Medvedev, who declared that he earned 3.3 million roubles (~$106,000) in 2009, owns a flat in the super-élite Zolotye Klyuchi apartment complex, where the maintenance charge alone is at least $5000 a month. The watch Medvedev wears costs $32,200. The president’s and the prime-minister’s suits come from Brioni and Kiton (these go for €5000-7000 a shot) and are what Russia’s billionaires prefer. Against the backdrop of the collapse in road-building and of much of the country’s infrastructure, our country’s leaders are building and restoring residences for their beloved selves out of the state budget (see http://svpressa.ru/society/article/21459/). They already have 13 of them dotted about the country! A presidential residence costing 7.7 billion roubles (a cool quart-million bucks) is being built on the Gamov peninsula in beggarly Primorsky Krai. The Konstantine Palace was restored at a cost of about $200 million early in Putin’s presidency. But the record for “effective” use of state must must be held by Medvedev’s beloved Meyendorf Palace on the Rublevka. Over $100 million was spent on restoring this 1300 square metre property – over $80,000 (not roubles!) for each square metre (see http://newtimes.ru/articles/detail/3625), a monument to corruption in the age of Medvedev. The active residences all together cost the budget billions of dollars annually.

Corruption has eaten up the largest megaprojects of the Putin era. Even Transneft admitted to corruption problems in the construction of the Eastern Siberia — Pacific Ocean pipeline. (“Corruption thrives at the ESPO”, Rosbalt, 2 July 2008). In March 2010, a major scandal broke out among the higher leadership, leading to the resignation of deputy minister of the regions Sergei Kruglik, over misappropriations in the construction of the Olympic sites. (“Misaccounting Payback”, Kommersant, 6 April 2010).

While gabbling about fighting against the “revenge of the oligarchs”, Russia has witnessed the enrichment of a new and mightier Putinocracy. The number of billionaires in Russia doubled during the difficult year of 2009.

This criminal system must be destroyed. We need to radically reduce the power of the civil service and cut back their authority. The state needs to stop thinking it has the right to non-state functions such as controlling enterprise.

Terms for civil servants should be set at all levels of the service. This is needed so that officials cannot become entrenched in alliances with private enterprise. The universal principle should hold that, having served for 8 years, the civil servant retire, with no possibility of a “third term” or other chicanery for staying in power (such as moving from president to prime-minister).

Officials caught acting corruptly should be disqualified for life.

We need radically new law enforcement and an independent Federal Investigation Service in which there is no room for people with links to corruptioneers.

We need strict civil control over the government’s actions, the abolition of censorship in the federal TV channels, and normal conditions for the political opposition. The people should be able to freely discuss such subjects as corruption in government and demand that criminal charges be brought against corrupt officials.

An important precondition in the fight against corruption is that Russia should have independent courts. There is no way in which corruption cases will be heard objectively and the guilty punished while the courts remain under the control of the executive.

The Country is Dying Out

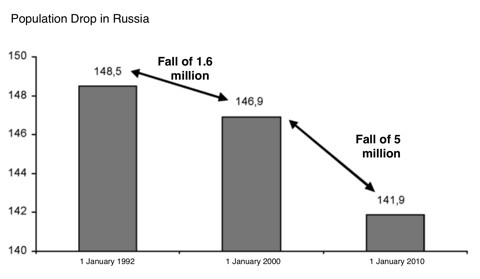

Putinist mythology would have it that we are seeing successes on the demography front, that the birth rate is rising, and so on and so forth. This is compounded by spreading another myth that the country “was dying out in the 1990s”. Let us look at the facts.Our population at 1 January 1992 was 148.5 million people, at 1 January 2000 it was 146.9 million. (Table data from RosStat). The drop between these two dates was therefore 1.6 million. At 1 January 2010, Russia’s population numbered 141.9 million, giving a drop of a whopping 5 million between 2000 and 2010!

The bitter truth therefore is that Russia has been losing 500,000 people a year over the last decade, a rate that bears no comparison with even the 1990s.

The main reason that our population is declining is supermortality. Around 15 per 1000 die every year. In July 2009, Russia could be found 12th from the bottom in the global mortality listing. (Source: CIA World Factbook). Our neighbour on the list are Nigeria, Zimbabwe, Chad, Somali. We have been maintaining African mortality levels in our country for many years now.

When it comes to life expectancy, our neighbours change. Here we rank 162nd with a life expectancy of 66 years, trailing behind Papua New Guinea, Honduras, and even Iraq (rank 144th / 70 years). The matter that screams out loudest from RosStat’s figures is male life expectancy: this stands at 61.4 years! (Average life expectancy in the EU countries is 79 years, in the USA 78, in Canada 81, in Japan 82.)

Russia’s birth rate is more or less normal for an European country – 11 births per 1000. (Remember that meanwhile we have 15 deaths per 1000).

In poorer countries, too high a rise in birth rates, especially in low income groupings encouraged to have more children through Putinite measures such as the “birth capital” allowance, can have negative consequences, lowering the overall standard of living and levels of care for the new-born and leading to high sickness rates. (Note, however, that the “birth capital” allowance of 250,000 roubles could buy one a mere 3-4 square metres of housing, based on average housing prices according to RosStat).

In April 2008, Minister of Health Tatyana Golikova was forced to admit that increased birth rates had led to increased infant mortality in 48 of the country’s regions. (in a speech to a plenary meeting of the ministry on 25 April 2008).

The problem is supermortality. The Russian government does not care for its population. One million six hundred thousand babies are born every year while 2,100,000 people die.

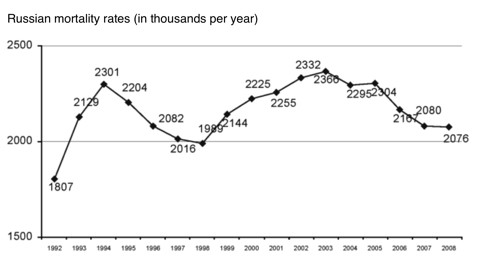

Russian mortality rates began to rise in the 1970s under Brezhnev and continued to do so right up to the mid 1990s. In 1995, mortality began to decrease and fell to under 2 million a year in 1998.

Under Putin, however, rates rose again and accelerated to reach a new peak in 2003, when 2.37 million deaths were recorded. The rate has not dropped below 2 million since then.

Russia’s exceptionally high mortality is the result of a concatenation of reasons. Nearly 60% of deaths are recorded as from cardiovascular causes, another 15% from cancer. Respiratory organs and digestive tracts claim another 4% each.

Russia is outstanding for its number of deaths from external causes – 12.5% of the total or more than 260,000 people annually. This is approximately twice as many as in China or Brazil and 4-5 time more than in Western countries.

The main external causes of death in the country are murder, suicide, and traffic accidents. The main explanation for so high a death rate from external causes are low levels of personal safety precautions, wrong lifestyles and poor quality of life, and the generally unhealthy situation in the country.

Russia ranks 19th in the world for its murder rate: 16.5/100,000. Our neighbours here are Ecuador, Swaziland, and Iraq. For Europe, we rank #1 and we also beat the USA, with an annual 6 murders per 100 thousand, by a wide margin. (Source: Global Burden of Armed Violence (GBAV) report, released in 2008 by the Geneva Declaration on Armed Violence and Development (www.genevadeclaration.org) and other national statistics).

Suicide is an even more serious problem. Over 41,000 commit suicide every year in Russia. This is twice as bad as Europe and three times as bad as the USA.

Too many people die in traffic accidents. According to Russia’s traffic police, there were 30,000 deaths on the roads while over were 270,000 injured.

Supermortality also comes from high levels of sickness in the population. The main reason for these health problems are our generally bad lifestyle, the lousy environment, and, very importantly, substandard medical treatment. Poor public health remains a serious problem which Putin was unable to make the effort to improve during the last decade with its rich windfalls.

What do average Russians think about what has been done by Putin and Medvedev in this field? A poll by the Levada Centre collected opinions on the national public health service in August 2008 and found the following:

• 66% of Russian believe that they will not receive good medical treatment when they need it;

• 58% are not satisfied with Russia’s public health system.

In fact, the statistics show that sickness rates have been rising in Russia. The latest statistics from RosStat only go as far as 2007, but these show a rise from a 2000 base of 50% in cardiovascular diseases (Russia’s main cause of death) from 2.4 million to 3.7 million and 17% for cancers – from 1.2 million to 1.4 million.

Russia ranks between Morocco and Ecuador (112 to 114th places) in its spending on public health – 5.3% of GDP as against 9-11% for many Western European countries. (Source: World Health Statisitics, WHO, 2009). The 2009 planned budget allocation for public health, physical culture and sport was a mere 325 billion roubles. For comparison, a trillion – three times as much! – was allocated to law enforcement and the special services.

Conclusion: the state apparatus, state corporations, and the specials services are far dearer to Putin that the health of the Russian people.

The authorities have tried to get away with low-cost one-off offerings such as the much-vaunted “National Project: Health” instead of systemic reform to create a working national health insurance system.

Alongside the poor quality of medical aid, another key reason for Russians’ supermortality is drunkenness. Even the authorities admit this is the case. Here is an excerpt from a resolution (#46 of 29 June 2009) of Chief of Public Health G. Onischenko entitled “On the Supervision of Alcohol Production”:

“Real per capita consumption of alcohol, accounting also for alcohol-containing substances including perfume, household products, and other similar, is over 18 litres of pure alcohol per person per year.

According to medical statistics, 2.8 million Russians, or 2% of the total population, have serious alcohol problems that affect their health…

In 2008, mortality from alcohol-related causes (RosStat data) amounted to 76,268 persons…”

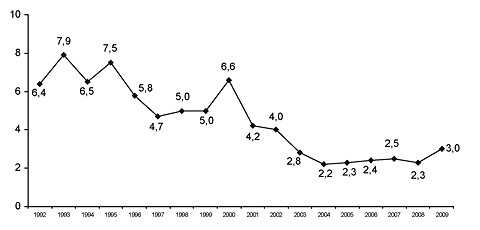

Just consider Onischenko’s figures! Eighteen litres of pure alcohol per person per year! RosStat’s official figure, by the way, is 9.8 litres. The rest of the alcohol consumed must therefore come from unofficial sources – from various sorts of moonshine with their related dangers to health.

The World Health Organisation considers that consumption of alcohol in quantities of over 8 litres per person per year is the critical level beyond which mortality from this cause rises. Russia’s consumption is over twice this level! It has been estimated that alcohol is the cause of the premature death of up to 700,000 thousand Russians every year. (Source: A.V. Nemtsov, Alcohol-induced Deaths in the Regions of Russia, an information bulletin of the Centre for Demography and Human Ecology of theRussian Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Population Studies, Issue 78, 2003, pp 1,2).

One in three Russians die from alcohol-related causes. Alcohol is yet another another reason for our supermortality.

For comparison, it should be noted that RosStat’s figure for alcohol consumption in 1999 was 8 litres per person per year with a true consumption rate of 14.5 litre per year. (Source: A.V. Nemtsov, The Lethality of Russian Drunkenness, Priroda Magazine, Issue 12, 2003, p. 11). Both official and unofficial figures therefore confirm that alcohol consumption has risen by about 25% under Putin.

Further tens of thousands of Russians die because of drugs. In June 2009, Anti-Narcotics Head V. Ivanov spoke of 30,000 deaths annually due to narcotics. (Source: Speech at Anti-Narcotics Committee meeting, Moscow, 26 June 2009). He mentioned the following frightening facts:

• Russia has between 2 and two-and-a-half million drug addicts with a main age range of 18 to 39.

• The average age of death for a drug addict is 28.

• 80,000 “new recruits” join Russia’s army of addicts every year.

• Russia has 5-8 times as many addicts as the EU states. Hard narcotics consumption is amongst the highest in the world.

In September 2009, the United Nations Commission on Narcotic Drugs published a report on Aghan opium in which it noted the following dreadful figures about Russia: the country annually consumes 75-80 tonnes of Afghan heroin, the number of addicts has risen tenfold in the last 10 years, and 30,000 people die from narcotics every year. This last figure is more that the Soviet Army’s losses for 10 years of war in Afghanistan. One should also compare these figures with European deaths from hard drugs – 5-8,000 deaths per year.

Furthermore, all this happening after Putin in 2002 set up a special body responsible for combating the spread of narcotics – GosNarkoKontrol.

Another serious Russian problem is that of smoking. The habit is very widespread. According to RosPotrebNadzor (Russia’s consumer body) 65% of men and 30% of women smoke and of these 80% and 50% respectively started in their teens.

Smoking is a cause in 27% of cardiovascular deaths in men, 90% of lung cancer deaths, 75% of deaths from other respiratory problems. Around 25% of smokers die prematurely: smoking on average reduces life expectancy by 10-15 years. (Source: RosPotrebNadzor statistics).

Cigarette sales have risen by 25% in the last ten years in both absolute terms (430 billion cigarettes last year as against 335 billion in 2000) and relative terms (3,000 cigarettes per person per year now as against 2,400 in 2000). The situation is radically worse than in the 1990s when cigarette consumption was half what it is now.

What has Putin done to redress this situation, to combat alcoholism, drug addiction, smoking? Not one thing.

Attempts to combat alcoholism by prohibition such as under Gorbachev and in Tsarist days failed. Today, the government is again talking about the need to combat alcoholism. Yet the strangest things are being done in this cause: from 2010, the government has decided that excise tax on beer will be tripled while only raising it 10% for vodka. It’s clear what this will lead to: strong spirits will be used to replace beer; drunkenness will rise. What were the authorities trying to achieve – improve the nation’s health or the bank balances of the vodka lobby?

How should one combat alcoholism? Our reply is by developing the middle classes. Alcohol consumption in Russia is a social phenomenon on the one hand and a tradition on the other. Research has been conducted that indicates a U-shaped dependency between quantity of alcohol consumed and income: the poor drink more (to drown their sorrows) and the rich drink more (consuming for kicks), while down at the bottom of the U the middle classes consume little alcohol and lead a healthier lifestyle.

There is even a phenomenon known as the French paradox. France is one of the world’s heaviest drinking countries, with a personal consumption of alcohol 11 times that of the USA. Nonetheless, France has more extremely long-lived citizens than anywhere else – 2,546 citizens over the age of 100 and an average life expectancy of 80. This all derives from France’s culture of alcohol consumption, from the fact of not consuming a great deal of spirits and staying with quality wine.

But drinks of good quality are only an option for those with the money to buy them.

That is why we insist that alongside publicising healthier lifestyle choices, we should also stimulate and support the middle class. To do this, of course, will require changing the nature of the country’s economic policies. (Discussed in greater detail in our sections “Country of Screaming Inequality” and “Raw-Materials Appendage”.)

As far as combating smoking is concerned, there is no need to invent solutions – one simply needs to look at how this was done successfully in the US and in Western Europe over the last decades.

The population decline is going to be a long-term one. Russia has recently been losing 1 million able-bodied people a year and will continue to do so at this rate for some time to come as a result of high mortality rates and natural ageing of the population. The loss of a million able-bodied people is the equivalent of a drop of 1.5% of GDP. It also reduces contributions to the budget and to pension funds, which in turn inevitably leads to pension payment problems and a consequent rise in social tensions. Chronic depopulation therefore constitutes a real threat to the country’s economic development, will in all likelihood lead to worsening standards of living, and may even bring into question the country’s size and territorial integrity.

The authorities will inevitably have to look to an effective migration policy to fill the holes in Russia’s force of qualified and unqualified labour in order preserve Russia as a state.

On the contrary, however, the Putin régime in 2002 passed a repressive migration law which on the one hand increased the numbers of illegal immigrants and on the other reduced the flow of law-abiding and able-bodied people into the country. About 8 million Russia-speaking citizens of the post-Soviet republics flowed into the country in the 1990s. After Putin came to power, the influx dropped off.

This sharp drop in the number of migrants during Putin’s rule is one of the reasons for the collapse in Russia’s population numbers as compared to the 1990s.

Russia: Raw Materials Appendage

When “Putin — The Results”, the first edition of our report, was published back in February 2008, Putin was happily boasting about economic successes. On 8 February 2008, he addressed a sitting of the State Council. Talking about the results of his presidency, he made much of the facts that GDP had risen during it and that in 2008 alone Russia had attracted $83 billion on inward investment.

Even then, however, we warned that the economic model being constructed by Putin was just a speculative bubble that could burst at any moment. And that is precisely what happened six months after our report was published: a massive economic crisis broke in Russia in 2008, a crisis far worse than the 1998 default, one which if it is to be compared with anything, then only with the period of the collapse of the Soviet economy and the economic depression of 1992-1994.

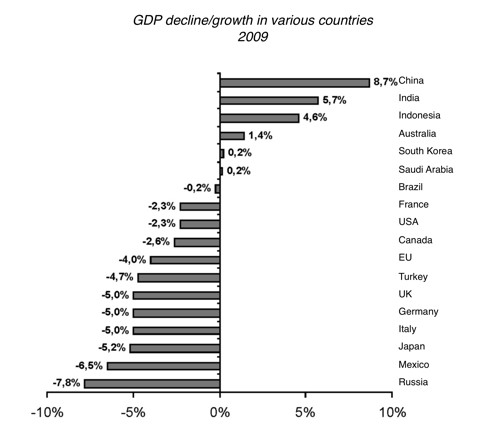

In 2009, Russia GDP fell by 7.9%. That is a record. The 1998 default happened after a smaller fall – 5.3%. This drop is on a par with 1992-1994.

Why did the Putinomy collapse so fast? In his attempts to cover up the failures of his economic policies, Putin tried to put all the blame for the crisis on America. But that does not help explain why the rate of decline of the Russian economy was far more severe than that that of the leading Western countries or indeed of the other countries of the BRIC. Russia came out as one of the 15 countries that suffered the most from the crisis.

The explanation which is usually pushed is that in 2009 Russia was still wallowing in oil dependency, relying on its oil and gas exports and the world price of oil. There’s plenty of truth in this. But in that case, how come Saudi Arabia, the world’s largest oil producer, whose economy is even more dependent on oil than Russia’s, not only did not suffer a fall in GDP but actually manage a slight growth – of 0.2%?

The decline is Russia was one of the sharpest seen in the CIS. In fact, 8 of the 12 CIS actually achieved economic growth in 2009! Apart from Russia, only the Ukraine, Armenia, and Moldavia suffered declines.

Yet while the economy trends ever down, Russia retains relatively high inflation of 9% a year, while in Western Europe prices are not rising at all and in the US, Japan, and China they are actually dropping.

What sort of economic monster has Putin actually built that it can produce both deep depression and high inflation simultaneously?

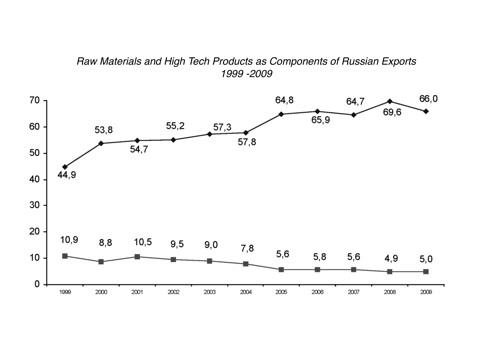

All these years we’ve been forced to listen to endless empty talk of the need to “make the economy less centred on raw materials”. And what has happened? Look at the table below. Raw materials made up 44% of Russian exports in 1999. More recently they have constituted 66-69%. Exports of manufactured goods and equipment have dropped from 11% to 5%.

While Putin has been ruling the country, Russia has become even more of a raw materials appendage to the world economy than ever before.

Putin’s “economic miracle” for his second presidential term was built on the influx into Russia of short-term speculative money from abroad. This did indeed lead to the high economic growth rates of 2005-2008 when over $140 billion flowed in. But this money was mainly in the form of loans. So when the crisis started, capital poured back out of Russia and the “economic miracle” finished.

Putin’s growth model was rickety because it was not founded on investments in modernising production, increasing labour productivity, or conducive to the development of small and middle business.

Economies like this can only “rise from their knees” if they get constant injections in their joints in the form of cheap credits from the West.

Looking back we can therefore see for ourselves that the main myths of Putinite economic success were outright lies. Russia’s development rates did not stand out in any particular way from the other CIS countries. This means that the economic growth of the 2000s was more probably the result of the post-Soviet countries ridding themselves of Soviet economic ways. Growth rates in oil-rich Russia were amongst the lowest in the CIS. Back in 2000, Russia enjoyed the 2nd highest GDP growth rate in the CIS. By 2008, it was in 8th place. By 2009, we led the pack for rate of decline.

Having been granted a spectacular gift from heaven – unprecedentedly high oil prices – the Russian economy should have grown considerably faster. Export oil prices were three times as high under Putin as they had been under Yeltsin (average $47pb in 2000-2009 and $60-90 during 2006-2009 as against $16.7pb in the 1990s).

With a windfall such as this, our economy should have shown growth of 9-15% a year, like our oil-exporting neighbours Kazakhstan and Azerbaidzhan.

Furthermore it is not Putin we have to thank for what economic growth we did show. All he did was hitch onto the positive trends that had appeared before he came to power. Economic growth resumed in Russia as early as 1997 and then again, after the default, in 1999, when the country GDP grew by 6.4%. Putin had nothing to do with this.

If only the last decade had been used to really modernise the country, to make long-term investments in the renovation of industry, to build roads and airports, to create a modern army and pension system… We may never again be presented with such a chance and painful changes (for example, pensions reform) will be far harder to carry out.

Structural reforms were needed in order to modernise. But everything was done back to front and inside out: assets were expropriated – from Yukos to Sakhalin-2 to Euroset while more and more was spent on paying for the growing apparatus of state, the special service, and financing the newly reformed state corporations.

Putin began the 2000s with a budget surplus and and ended the decade with a growing deficit (which in 2009 amounted to 5.9% of GDP). How to patch the holes? Putin found an answer: raise social security payments and the pensionable age. Russia also went back to borrowing abroad.

At the same time and paradoxical as this may seem, tax on the oil-and-gas sector is being reduced. In 2009, Putin offered tax breaks worth over $6 billion to the oil industry and again refused to increase tax for Gazprom, although the corporation pays considerably less in tax than do Russia’s oil companies (for more detail see our report “Putin and Gazprom”). In the deal called “Gas in Exchange for the Black Sea Fleet”, Putin released Gazprom from $4 billion a year in taxes. We citizens of this country will pay for this in higher taxes and utilities bills.

The measures claimed to have been taken by Putin in connection with the crisis are revolting in their one-sidedness. They make it perfectly clear that the banking sector and a small circle of corporations have been prioritised to receive the greater part of this aid. Instead of supporting the people, Putin has provided financial aid to oligarch O. Deripaska to the tune of $4.5 billion and another $1.8 billion to his friend R. Abramovich. Meanwhile, Rosneft friends Sechin and Bogdanovich received $4.6 billion in aid from state banks.

And we, the people of Russia, will be doing the paying to keep afloat the corrupt unreformed raw materials appendage they have built.

Dead-End in the Caucasus

The Caucasus has played a key part in raising Putin to Olympian political heights. Immediately after he was appointed prime-minister in 1999, Putin initiated military engagements against Chechen separatists and memorably promised to “slaughter them in their outhouses” [TN: the Russian phrase “zamochit v sortire” is intended to sound crude but does not really have much meaning – I would have gone for “drown them in their own sh*t” in a literary translation. This manner of speech is much more “Putin”.] Riding the terrorism wave, Putin got the support of a large number of people and became president in Spring 2000.

For the rest of the decade, the myth has carefully been cultivated that Putin pacified the Caucasus and beat the terrorists. In 2007, Putin declared that “ international terrorists’ aggression has been stopped in its tracks thanks to the courage and unity of the people of Russia.”

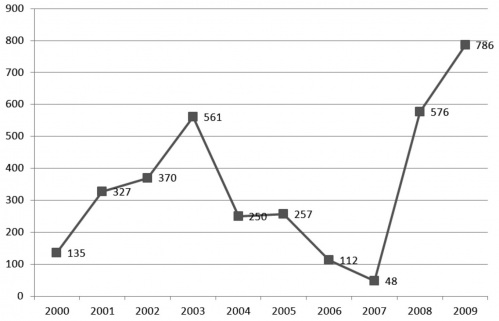

Quite the opposite, however, is true. Below you will find a table listing numbers of acts of terrorism over the last decade. This table has been assembled by us from data officially promulgated by spokesmen for law enforcement and the specials services.

The table clearly shows that. starting in 2007, the number of acts of terrorism shot up, rising more than 12-fold between 2007 and 2008, and by half as much again in the following year.

That were are being lied to about having “beaten the terrorists” is plain for all to see from the fact that there were 135 recorded acts of terrorism in 2000 at the start of Putin’s reign but 786 in 2009-2010, a six-fold rise.

The Moscow metro explosions on 29 March 2010 demonstrated that the Russian special services are not just incapable of stopping terrorism in the countryside – they can’t even prevent it yards from their HQ!

The reasons for the special services’ lack of professionalism and general helplessness comes from the way they set their priorities.

The top priority is to maintain and secure Putin’s personal power and that of his group. This has led, for example, to the rebirth of political repression – witness the recently established and already infamous Dept. “E” to combat extremism, which is used to spy on and set up opposition leaders – and also to the fabulous increase in the numbers employed in the specials services and in the OMON riot police used to disperse opposition meetings and demonstrations wherever they may occur in Russia.

Their next priority is to provide protection for business, take part in raids, and engage directly in commercial activities.

A letter by some OMON servicemen to the New Times shockingly broke this story open. (Slaves of the OMON, New Times, 01.02.2010). It is evident that, for all their huffing and puffing to the contrary, combating terrorism is by no means a priority of Putin’s special services. This is despite the fact that federal budget expenditure on security and law enforcement has risen more than tenfold from $2.8 billion in the 2000 budget to $31.3 billion in 2009. Budget expenditure on the special services is more than three times as great as spending on public health and education taken together. The total number of people employed by the special services is now over 2 million, twice as many as there are servicemen in the military. Not even in Soviet times was such a thing ever seen.

Another reason for the striking rise of terrorism in Russia is the failure of Putin’s Caucasus policy. This policy is founded on the idea of using loyal and at the same time corrupt clans to run the Caucasian republics. Things work out a bit differently on the ground and in reality this amounts to “I give you money and you give me loyalty (including 99% voting for United Russia in the elections) and deal with terrorism”.

The result has been disappointing, to say the least. The Caucasian republics are de facto places when neither Russian law nor the Russian constitution rule, with unlimited power held by greedy and corrupt groupings whose loyalty is purchased with funds from the federal budget.

The Russian budget (which is the same as saying “you and I”) allocates stupendous sums – $4.5 to $6 billion a year – to régimes which have on the one hand become to all intents and purposes sovereign states but on the other have shown themselves incapable of ensuring security within their territories or further afield in Russia as well. (Federal Funding Accounts for 86% of the Budgetary Income of Ingushetiya, nearly 60% of Chechnya’s, about 75% of Karachaevo-Cherkesya’s, 75% of Dagestan’s, nearly 58% of Kabardino-Balkaria’s, 56% of Northern Ossetia’s, and 48.5% of Kalmykia’s, Lenta.ru). Not for nothing did London exile Akhmed Zakayev, former high official in Chechnya and now well-known separatist, declare publicly that Ramzan Kadyrov has realised the dream of Dzhokhar Dudayev and Aslan Maskhadov of creating an independent Chechnya that also receives vast sums of money from the federal budget.(The Zakayev Romance, S. Markedonov, in From Our Own Correspondent at http://www.chaskor.ru/p.php?id=9058).

We link the increase in terrorism in Ingushetiya and Dagestan in the main with Putin’s major mistakes in his appointments of heads for these regions. KGB General Zyazikov’s many years of rule as president of Ingushetiya ended with a sharp rise in terrorism and islamic fundamentalism in that republic. The federal authorities for a long time managed to turn a blind eye to such events as the blowing up of a police HQ in Nazran, the murder of Magomed Yevloyev and other rights activists and opposition leaders. It was only when the situation in Ingushetiya finally began to spin out of control and there was already talk of Ingushetiya seceding from Russia that Zyazikov was removed from power, to be replaced by Yunus-bek Yevkurov, who soon himself became the victim of an attack. It is now evident that the metastases of terrorism and islamic extremism have spread so far and so deep that no Yevkurovs or Khloponins are going to solve the problem.

Much the same happened in Dagestan. Mukhu Aliyev was appointed president in 2006 but is clearly a weak figure, with a reputation for corruption. The republic now witnesses near daily attacks and terrorist incidents. Dagestan has to all intents and purposes been in a state of civil war for the last few years.

So what do we have today? The separatists’ aims have been essentially realised and islamic fundamentalism, fed by high levels of unemployment, poverty, total corruption, and complete unlawfulness, is on the rise in the Caucasus. For this, Russian meanwhile pays billions of dollars a year and sacrifices the lives of innocent civilian victims to terrorism.

The Northern Caucasus has become Russia’s Palestine. The situation is at en even deeper dead-end that it was at the start of our “national leader’s” rule.

We should also note that Putin has used the most shocking acts of terrorism to reinforce his personal power and to trample on human rights and freedoms. The Dubrovka theatre incident in October 2002 was used to excuse the closure of the independent TV channels NTV and TV6. After the Beslan tragedy of 2004, Putin abolished the election of governors and single-mandate standing for election to the State Duma. Repressive laws were passed to make things harder for the opposition and elections became a farce pure and simple.

Oh Dear, The Roads

We all know that the bad state of our roads roads is one of Russia’s major headaches.

In our first report on the results of Putin, we described in detail the degradation of the road infrastructure under his presidency. The very fact that the rate of road-building dropped during the “fat” years is a disgrace. China in just 20 years has built itself a modern highway network: in 1989 the Chinese had just 147 kilometres of motorway, today they have 60,000.

Meanwhile, in Russia the road-building industry is going down the drain.

Back in the wild 1990s, we were commissioning an average of 6,100 kilometres of new highway a year. Since 2003, under Putin, that is now no more than 2-3,000 kilometres.

Roads Commissioned Year on Year (‘000 kilometres)

Federal highways saw least growth of all: 1,159 kms added in 2009; 560 kms in 2008; ~400 kms in 2006-2007, and a mere 169 kms in 2005.

The quality of Russia’s road is terrible as well: two thirds of federal highways and 76% of others do not meet the official standard. Of the so-called federal highways, 92% have only 2 lanes and over half of them have poor surfaces and foundations. The number of vehicles on our roads has more than doubled since the mid nineties while total road length has actually reduced. Russia’s roads are in the main laid on the cheap with a single layer of asphalt over one layer of gravel and one of sand. Such surfaces need running repairs every 7-8 years and major repairs every 14-15 years. Europe has long used roads laid on concrete foundations that need overhauling only every 30 years or so.

The total length of Russia’s official federal highways is just 49,000 kilometres, of which only 23,000 kms are rated Category 1 and 2 – not less than 2 lanes [TN: 1 in each direction] and width of not less than 7 metres, so that driving speed can reach 100 km/hour. Compare this with the United States whose interstate highway system alone runs to more than 75,000 kms in length.

The US national road system includes more than 265,000 kms of quality highways in a total of 4,200,000 kilometres of hardtop. (Cf Russia with just over 700,000 kms).

Bad roads are one of the main factors holding back development in Russia due to higher transportation costs and the difficulty of moving goods and people about the country. RosAvtoDor [TN: the road authority] estimates that the insufficient development of the road system annually costs the nation 550-600 billion roubles (1.5% of GDP) in lost income. (Source: Main Concepts for a Reformed Road System in the Russian Federation, RosAvtoDor).

China has in recent years spent an overage of $18 billion a year on modernising its road system. Such an amount could easily be found in Russia’s bountiful budget. But Putin has preferred to spend the money on other things – increasing the size of the bureaucracy, financing the special services, stuffing the pockets of the state corporations… It is hardly surprising that China’s is developing faster than we are.

At the same time and paradoxically even the money allocated to road-building is not leading to anything good: corruption in the civil service means that a great deal of it is simply stolen. Consider the figures below.

In 1999, federal budget spending on road renovation and building of new highways amounted to 8.7 billion roubles ($350 million at the then rate of exchange). This bought 321 kilometres of new federal highway. Cost: about $1 million per kilometre.

In 2009, 230 billion roubles ($7.2 billion at 2009 rates) were allocated. This bought 1,159 kilometres of new federal highway. Cost: $6.3 million per kilometre.

Let us leave the question of the quality of the roads in Russia aside and just look at cost. In the US, the construction of 1 km of 4-lane highway costs $4-6 million. In Germany it costs €8 million to lay a kilometre of first-class autobahn. In China highways cost $3 million per kilometre and in Brazil $3.6 million.

Given the appetites of our road agency’s bureaucrats and of the subcontractors servicing them, there will never be enough money in the whole of Russia for us ever to get a proper road system.

In 2009, the authorities announced that as a result of emergency budgets cuts, we would be reducing expenditure on road maintenance, repairs, and development by a quarter, from 434 billion to 343 billion roubles.

A further cutback to 274 billion roubles is planned for 2010. (Source: report of RosAvtoDor head A. Chabunin at the All-Russian Conference for the Review of Results and Prospects for Highway Development, Moscow, 10 March 2010). Subsidies for road building from the federal budget to the regions will be reduced to 37 billion roubles. Financially, road building is in a state of collapse.

Ten years is quite long enough to be able to see if a politician is capable of resolving a problem. It is totally obvious that Putin, despite the oil windfall, has failed utterly in the matter of Russia’s roads.

A country of screaming inequality

Total inequality and the deepest of divides within society and between the regions are the hallmarks of Putin’s Russia.

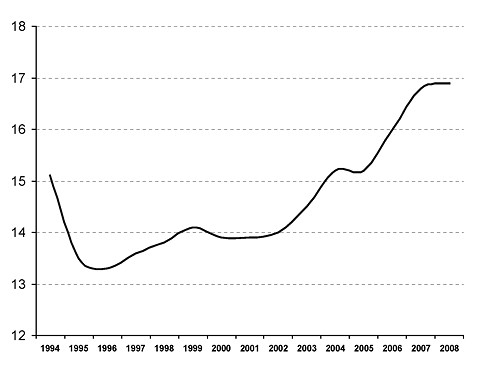

Social inequality stands first and foremost amongst these. Economic growth under Putin was accompanied by increasing social divisions. At the end of the 1990s, the income differentiation coefficient was 12-13, i.e. the average income of the richest 10% of the population was 12-13 times as great as the poorest 10%. By 2000, it was 16.9 times as great, an increase of over 20%!

No greater income differentiation coefficient has ever been recorded in Russia’s modern history. Furthermore, differences of such magnitudes are not characteristic of developed countries and are more commonly to be found only in 3rd world countries.

Income differention in Russia During the 1990s Under Putin (straight multiples)

Inequality between the regions has not lessened either. For example, the difference between the GDP per person of the 10 richest regions in Russia (Moscow, Yamal-Nenetsk, Khanti-Mansiisk, and others) and the 10 poorest (the republics of the Northern Caucasus, Tyva, Gorny Altai, Ivanovsk) was a factor of 6.2 in 1999. In 2008 it had not decreased at all and stood at 6.3.

The difference between the average salary in the 10 richest and poorest regions stood at a factor of 5 in 1999. Although this did drop to a factor of 4 by 2008, one would have thought the country could have done better than than in a decade.

Salary statistics for Russia show that there are 20 or so regions where the average salary is equal to or above the mean for Russia as a whole (approximately 17,300 roubles per month in 2008). Besides Moscow and St. Petersburg, these are generally speaking the oil-and-gas rich regions (Yamal-Nenetsk, Khanti-Mansiisk, the Nenets Autonomous Region, Sakhalin, and the Tomsk Region) and regions with other natural resources (Krasnoyarsk, Yakutia).

The remaining 60 or so regions that Russia is divided into have average salaries of under 17,000 roubles per month. In the Northern Caucasus, salaries average 7-9,000 roubles per month. In the Central Black Earth Regions – 10-13,000 roubles.

Meanwhile, Putin’s Russia has been beating all previous records for growth in the numbers of its billionaires. Back in 1999-2000, Forbes’ international list did not contain a single Russian billionaire. In 2010, the magazine “Finans” reckoned Russia had 62 people with a fortune of over $1 billion. Among the leaders of the pack one finds Roman Abramovich, richly paid for Sibneft, (in 4th place with $11.2 billion) and Oleg Deripaska (5th, $10.7 billion). The latter was beneficiary of a massive rescue package from Putin to help him through the crisis. The billionaires include such close friends of Putin as Timchenko, the Rotenberg borthers, Kovalchuk (see our chapter on corruption in Russia). Putin and his buddies have certainly not wasted their time during the last 10 years.

The Putin system sees to it that his friends and those close to natural resources get richer. It is only in those parts of Russia which have access to income from the export of raw materials that people are able to have a standard of living on a par with that of people in the European Union.

While the rest of the country lives on a par with people in, say, Mexico.

Our statist-monolithic economy, built around the exploitation of our country’s natural resources, is the main reason for these social and regional divides. Smaller businesses not connected with natural resources in the regions without such are simply not able to grow adequately – because of the high barriers put up by officials and the monopolies they are linked to, because of the taxation war waged against them, because of the high risk of having their businesses snatched from them, and because of poor infrastructure.

Yet another reason is the result of changes in the distribution of the federal budget. Back in 2000, this was expended in approximately 50/50 fashion between the centre and the regions. Today, the share is 65/35. Contributions that previously went to the regions have been diverted to the salaries of state officials. This has in fact increased average income levels in the regions, but…

In order to overcome differentiation, it is extremely important to support economic activity, to open regions for investment, to develop small and medium business, to involve ever more people in enterprise. That is the only way in which large numbers of Russians will ever be able to become rich. During Putin’s presidency, however, the number of small enterprises in Russia has hardly risen at all and today stands at 1.35 million or fewer than 10 enterprises per 1000 population. Compare this to the EU where the figure is 45 per thousand, Japan – 50 per thousand, and the USA – 75 per thousand! Over half the population in the West is employed in small enterprises. In Japan it is nearly 80%. In Russia, small enterprises employ just 11 million people – a mere 16% of the total workforce.

The contribution of small enterprise to the country’s GDP is about the same at 13-15%. Compare this to the USA, where the figure is over 50% while in the eurozone it reaches over 60%.

It should be no surprise therefore that the people of those countries, unlike the citizens of Russia, lead lives of plenty and that the middle classes are large there. On the other hand, Russia is in 3rd place in the world after the USA and Germany for its number of billionaires.

If we want a country with a fairer economy and social system, we must first dismantle the criminal state monopoly capitalism that has arisen under Putin.

Pensions Breakdown

One of Putin’s greatest failures was the mess he made of pensions reform. When he came to power, Putin promised that he would give the country a modern pensions system that would provide the elderly with a decent income and at the same time not make for too great a burden on the budget.

This was achievable – if the country had gone over to a funded pensions system under which pensions are paid not from the contributions of the currently employed and the general budget but from accumulated contributions and the income derived from investing them.

The pensions reform has been a catastrophe. Despite the oil price windfall, pensions have stayed under the official subsistence level throughout Putin’s rule.

The distribution pensions system is cracking at the seams. Back when we published our first report on Putin, we predicted that Russia’s pension fund deficit would hit 1 trillion roubles by 2015.

But our gloomy prognosis was not gloomy enough: the deficit reached 1 trillion 166 billion roubles – 3% of GDP – in 2010! Funding pensions is one of the main drains on Russia’s federal budget today.

Since the budget was catastrophically short of the fat to pay pensions by the old system, Putin, in 2009, decided to:

a) freeze further salary hikes for government employees;

b) raise the unified social tax (UST), as Russia’s social security contributions are called, to 32-34% from 2011 while simultaneously abolishing the previous progressive scale for contributions.

This will obviously seriously hurt the pockets of all Russian taxpayers, to the detriment of the country’s economy. In this time of crisis, Putin has decreed that government employees will earn less (freezing salaries while inflation continues apace is equivalent to a pay cut). Internal demand will fall.

Another painful blow has been struck against business. Small and medium businesses not involved with natural resources will feel the most pain, along with those involved in innovation. (There’s your “building an innovation-based economy” for you!). Unlike in the raw materials business, in these spheres salaries are a major cost element and paying the increased UST will be particularly burdensome.

Raising the UST will leave Russia with one of the most burdened payrolls in the world. Does anyone remember Russian boasting back in 2000 that the country had “the lowest income tax in Europe”? Well, forget that now!

In order to deal with its pension fund deficit, in spring 2010, the possibility of raising the pensionable age was mooted. Of course, the idea of increasing life expectancy was something best left ignored.

The pension fund deficit is not the only problem that Russia faces in this field. The current distributive system (under which contributions by those in employment go to pay pensions to those in retirement) means that it is simply impossible for the pensions to be of a decent level. This can only be achieved when the ratio of actively employed to pensioners stands at about 3:1. In Russia today, that ratio is 1.7:1 and is set to drop to 1:1 around 2020-2030 as the population inexorably ages.

The situation could be saved by a quick and effective transition to a savings scheme. These schemes exist in all the developed countries of the West and have proved to be very effective. There, pension funds are built up and invested, forming large mountains. In Switzerland, for example, the fund so accumulated amounts to 122% of GDP, in the Netherlands, it’s 130% of GDP and even in the UK it over 70% of GDP.

The size of accumulated and invested pension funds in Russia is just 2% of GDP.

The creation of a savings scheme here resulted in a total failure, drowned in a sea of empty talk and sabotage. One of the main figures responsible for this failure was Mikhail Zurabov. He’s nonetheless doing fine himself, being currently Russia’s ambassador to the Ukraine.

In 2009, the authorities resorted to outright fraud in their attempts to fill the fund: a programme of state subsidy of pensions savings was announced under which people who contributed 1000 roubles of their salary to the pension fund would have another 1000 added to it by the state (with a maximum of 12000 a year). To the uninitiated, this sounded quite nice.

However, had the thousand roubles contributed by the employee been deposited in a bank account, the money could have earned twice as much as it did under this “government co-financing” scheme! [Source: a detailed description of the fraudulence of this scheme was written up in an article entitled “Who’s Co-Financing Whom?” which appeared in Vedomosti on 6.11.2009]. Those who joined the scheme simply lost hundreds of thousands of roubles as the whole thing was dreamt up in order to get people to pay 1000 roubles a month into the pension fund and so help it out somewhat.

And all the above is besides the corruption in the fund itself. In late 2008, former pension fund head Gennadi Batanov was charged with abuse of authority causing the fund to lose over 43 million roubles. The following year, a series of arrests on corruption charges was made in regional departments of the pension fund.

Thus instead of decent pensions we are witness to failed pension reform, an underfunded pension system, tiny pensions, and a Pension Fund that is corrupt through and through. At the same time, the workforce’s pockets are being plundered under a so-called programme of “state co-financing of pensions” even while it is likely that the pensionable age will will be raised.

Those are the true results of what a decade of Putinism has done to our pensions.

Crooked Billions

The pensions’ fund deficit, the degradation of the roads, and howling poverty (see previous chapters), all go to make Putin’s megamillion projects look all the more obscene. Let us look at three of these in greater detail: the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics; the North Stream, South Stream, and Altai pipelines; and the APEC-2012 (Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation) Leaders’ Summit in Vladivostok.

Organising a Winter Olympics in the Subtropics

Nikita Khrushchev is remembered as the communist party general-secretary who tried to grow corn (maize) around Murmansk, in Siberia, and in the Far East. This earned him the nickname of Cornflakes Nick.

Russia is a winter country. It takes some searching to find places in Russia that never see snow or ice. Putin found one such, however – the subtropical resort of Sochi. And then he decided that a Winter Olympics should be held there. One wonders what nickname Russians will invent for him: Summer Snow Vlad maybe, or something else? One thing no one doubts, however, is that these winter olympics will linger long in popular memory.

The initial euphoria at the IOC’s award of the Olympics to Sochi was rapidly replaced by dismay in general and serious grief in particular for many of the town’s inhabitants. Because the town’s very existence as a resort suddenly became uncertain, as did the futures and lives of thousands of its citizens.

Let’s take things in order:

• Expenditure on the Olympics will exceed $15 billion. More than half of this will be found from the federal budget. For the sake of comparison, the Vancouver Olympics cost $2 billion. Salt Lake City and Turin cost about the same. Almost half of the spend – 227 billion roubles – will go on the construction of a 50-kilometre highway from Adler (the airport) to Krasnaya Polyana, a road that will cost $150 million per kilometre!

• Most of the Olympic events will take place in the Imeretinsky lowlands [TN: called the Imeretinsky Riviera in Putin-speak], not far from the Black Sea shore, where six ice palaces and their attendant infrastructure are due to be built. This will require the eviction of over 4000 people from 400 private houses and 32 apartment blocks. Rehousing them has turned into a nightmare: new homes were erected for them in the village of Nekrasovka, using cheap and poisonous PVC building materials (the same stuff that caused the death of 150 people in the Khromaya Loshchad nightclub fire in Perm). The charge for these new homes was about $1 million each. However, the houses the relocatees had been forced to leave were valued at $300-400,000 at best and that was the only compensation they were offered. So not only are people being thrown out of their own homes where they and their parents before them had always lived, they are expected to pay for the privilege.

• The Olympic venues will have seating for 200,000. Sochi’s total population is 400 thousand. The venues will never be filled again after the 2 weeks of the Olympics. Sochi’s only stadium today – the Metreveli Stadium – has 10,000 seats and has only even been filled to capacity twice in the 40 years since it was built: the first time was for its opening ceremony and the second and last time was for an Elton John concert. Putin’s idea that three of the six venues will be dismantled and moved elsewhere after the Olympics resolves nothing. Sochi has no tradition of playing ice-hockey, skating, or skiing. As a result, venues that are much needed in central Russia will stand unwanted and unused in Sochi, left to decay or be turned into flea markets. Maintaining ice palaces and other winter event venues in a place as warm as Sochi will be an extremely expensive business. The small ice skating rink near the Riviera Park in Sochi costs $1 million a year to run. One can expect the running of the much larger ice palaces and their infrastructure to cost hundreds of millions a year.

• Sochi as a town suffers from a shortage of energy. It currently needs about 300 megawatts. The Olympic venues will eat up about 600MW, twice the town’s requirements. Who is going to pay for this, especially once the Olympics are over? Sochi’s and the Kuban region’s budgets can’t even cover the maintenance costs of these stadiums. The federal authorities will forget about the Olympic site as soon as the games are over. We will surely witness the creation of a true and long-lasting memorial to Putin’s wilfulness and spendthrift ways.

• The Olympic preparations are taking place with gross disregard for the environment. The Adler-Krasnaya Polyana highway is being laid through the unique Western Caucasus nature reserve and will lead to the extinction of some unique tree varieties and the destruction of the left bank of the Mzymti river. Complex geology (the many Karst faults) has made for difficulties in building tunnels and creating the track for the road. Mountain rockfalls have dogged the construction throughout. Nature itself is fighting back against this mindless and destructive project: in mid-December 2009, a storm washed away away the freight port that Deripaska had just built and the rapid Mzymti river flooded and engulfed road-building machinery.

• The influx of migrant workers, untold quantities of equipment, and incoming materials by the million tons are making things still worse for the town’s already overloaded transit system, which consists of little else besides a main road along the coast. The collapse of the transport system, overcrowding, and poor ecology are keeping holidaymakers away from Sochi, depriving the town of its sole source of income and the people of the rest of Russia of one of their favourite summer resorts.

The authorities prefer to maintain silence when asked what will happen to the Olympic venues after the event, what will be done for the people evicted from the Imeretinski lowlands, and why the environment and Russia’s last summer resort are being ruined for the sake of the Olympics. Butthe day will come when they have to provide replies and answer for what was done. We believe that it is perfectly possible to organise an Olympics without horror stories, to do things in a human way. Our detailed plan for holding the Olympics in Krasnaya Polyana and transferring certain parts of the games to other venues across Russia may be read in our report Sochi and the Olympics [available on www.nemtsov.ru and www.milov.info].

Crooked Pipelines

For over 10 year of his rule, Putin has been trying to make us believe that building transnational pipelines is a matter of strategic and geopolitical importance. The official propaganda would have it that the new pipelines will make Russia still mightier and Europe and China still more dependent on our hydrocarbons.

Look at them more closely, however, and it becomes apparent that these projects are swindles plain and simple.

Take, for example, the North Stream pipeline. Its first-stage capacity is 27.5 billion cubic metres a year and this is due to rise later to 55 billion. The officially stated cost of the project is $11.5 billion, though it will in fact cost no less than $15 billion. Putin’s reasoning for the pipeline is that it will help rid Russia of dependence on the unpredictable Lukashenko and the Belarus-Poland transit issue. Let’s turn now to South Stream. It has a first-stage capacity of 30 billion cubic metres a year, rising to an eventual 66 billion. It will cost no less than $25 billion to lay – across the bottom of the Black Sea through the territorial waters of Russia, Turkey, Bulgaria (while bypassing the Ukraine). This however will still not take away our dependence on Ukrainian transit, since 130 billion cubic metres a year are pumped to Europe through that country. So even if South Stream is used to its maximum capacity, that will still leave at least 60-70 billion cubic metres being pumped through the Ukraine.

The 2,300-kilometre-long Altai pipeline is to run through the mountains of the Altai nature reserve. Its capacity has been set at 30 billion cubic metres a year and will certainly cost no less than $10 billion.

All three pipelines are irresponsible acts of adventurism. First and foremost because production at Gazprom has stagnated for the last 8 years (2001-2008) at 540-550 billion cubic metres annually and actually fell sharply to under 500 billion (462 billion cubic metres, to be precise) in 2009.

The only major gas field to go into production under Putin is the Zapolyarnoe field. Old gas fields – Urengoi, Yambur, Nadym – are reaching the end of their useful lives. Delays dog the opening of the Yamal and Shtokman deposits. Not enough is being invested for anything real to happen soon.

The situation is therefore that pipelines are being built when there isn’t the gas to fill them, either now or in the foreseeable future. It’s quite conceivable that billions of dollars worth of pipeline will be left to rust, empty of gas, and no return earned on the money spent.

A second problem is that Gazprom is in financial difficulties. Inefficient and corrupt management and Putin’s incompetent interference in the company’s activities have led it into massive debt – about $50 billion, the equivalent of 1 year’s turnover. Diverting funds to pointless pipelines is only making Gazprom’s financial state worse.

Bypassing Belarus is not just super-expensive: it’s completely pointless. The fact is that Gazprom already owns 50% of BelTransGaz (Belarus’ gas transport system) and is therefore quite safe from any political risk connected with gas transit.

Gas transport projects involve colossal price risks. The pipeline to China provides a particularly clear example. China is unaccustomed to paying, and has never paid, European prices for its gas. The competitiveness of China’s economy derives not just from cheap labour but also cheap energy, derived in the main from coal. That China will pay more than $200 per 1000m3 is just not credible. Yet at that price level, the Altai pipeline will never be profitable. It should be recalled at this point that Gazprom is actually short of gas and has to buy it in from Turkmenia, to whom it pays $250-300 per 1000 cubic metres.

Sending gas to Europe also involves financial risk. Three of these are particularly important:

1) In Europe, more and more gas is being traded on the spot market, at prices considerably lower than those of Gazprom’s long-term contracts. If Gazprom tries to insist on long-term contracts at high prices, it risks losing the European market.

2) Cheap shale gas, as now being produced in the USA, has driven the price of gas down sharply there and the same is bound to happen sooner rather than later in Europe. Large deposits of shale gas in Poland mean that gas prices will inevitably drop in Europe and quite soon.

3) Gas consumption is being brought down by the introduction of new energy-saving technologies.

And so we have a situation where Putin is proposing to spend $50 billion on gas pipelines when firstly there isn’t the gas for them; secondly, they don’t actually resolve the transit-country problems; thirdly, they aggravate Gazprom’s already serious financial problems; and fourthly, they are far from likely to pay their way.

The APEC-2012 (Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation) Leaders’ Summit in Vladivostok

A meeting of the APEC countries is scheduled to be held in the city of Vladivostok in 2012. That a prestigious event of this kind should take place in Russia would seem to be a good thing. If only there weren’t a “but”…

According to the Ministry of Fiance, the cost of preparing for this summit has reached an astronomical 284 billion roubles, of which 202 billion will be disbursed by the federal budget with the rest of the money coming from the Primorsky Region (of which Vladivostok is the capital) and private investors.

The budget for this summit is greater than Russia’s total annual spending on roads for the whole country. It is also 4 times greater than the Primorsky Krai’s total annual budget.

We have a question: how is it that a summit can cost nearly $10 billion dollars or 5 times as much as the Vancouver Olympics? The answer is that Putin has decreed that the summit will be held on Russky Island – which is completely lacking in infrastructure, needs a bridge to be built to it, and then needs power stations, hotels and so on to be built on it. This furthermore is being done when Vladivostok itself could do with an upgrade, suffering as it does from a decayed infrastructure, inferior roads, broken-down utilities, and worn-out housing.

Two bridges to the island will span the Zolotoi Rog Bay and the Vostochny Bosfor Straight. These alone will cost over $2 billion even though the two together will not be more than 3 kilometres long. Note for comparison that China built its 35.6 kilometre long Hangzhou Bay Bridge for $2 billion while a bridge of similar length to ours was built in France for €394 million.

The forthcoming summit has furthermore become a major problem for the citizens of Vladivostok and the region as a whole. The regional authorities have had to cut back on social programs, pay rises for teachers, school meals, housing projects for young families, and more in order to finance this expensive venture. It’s obvious to all that the main beneficiaries of projects such as these are Putin’s corrupt bureaucracy and the businessmen allied to it, who stand to gain fat government contracts. There’s no other way to explain why building for the government always involves stratospheric prices.

The projects described above will cost about $75 billion. But there are more: Putin has a number of other costly and totally ineffective projects in hand. Any list would include the hastily built multibillion Western Siberia-Pacific Ocean oil pipeline. In just a few months from its commissioning, it has suffered three accidents and leaked hundreds of tonnes of oil. The project will never pay for itself and the damage it has done and will do to the environment is incalculable.